When a glass vessel is being blown, and thus is still in its heated state, its surface form as well as its shape can be manipulated in many ways. In Roman times glassmakers took full advantage of the decorative potentials of their medium. A major by-product of the invention of blowing was the invention of mold-blowing. Here, a molten gather of glass was blown directly into a mold of two or more sides. Using this technique, thin-walled vessels with complex figural or geometric patterns (sometimes including inscriptions) could be created repeatedly and quickly. The logo of the glass-maker Ennion frequently appears as part of the decorative scheme on his mold-blown vessels: "Ennion made me. Let the buyer remember him!"

Through mold-blown inscriptions such as these we glimpse something of the glass-makers themselves. Regrettably, however, inscriptions of glass-makers on objects other than their products are very rare. For all the interest taken by Roman authors in the qualities of glass, allusions to the people who created it are few and far between. One curious story passed down from Pliny to Isidore of Seville describes the fate of a glass-maker at the court of Tiberius (A.D. 14-37). The craftsman demonstrated to Caesar that he had invented a means of tempering glass so that it would not break when dropped but could be hammered back into shape like a bronze vessel.

When the man admitted that he alone knew of this new treatment for glass, Tiberius had him beheaded "lest when this became known, gold would be valued like mud, and the values of all metals be debased." To what could this tale possible refer? It is tempting to postulate that it has something (however obscure) to do with the invention of mold-blowing. If not the actual inventor of mold-blowing, Ennion was certainly one of the very earliest masters of the technique. An Ennion-signed cup found at Corinth in Greece in a sealed deposit together with a coin of A.D. 37-41 now provides us with a firm date for the early range of his career. It dovetails nearly with the setting of this peculiar story in the reign of Tiberius.

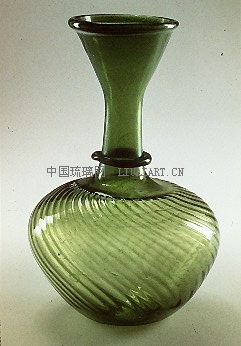

Although free-blowing did not offer the advantages of mass-produced uniformity that mold-blowing allowed, the decorative potentials of the technique were seemingly limitless. While free-blowing a vessel, the glass-maker could achieve a variety of surface effects by drawing the glass out in fin- or thorn-like projections, by pinching it, by ribbing it or corrugating it, or by indenting it at regular intervals. Once blown, a vessel could be decorated with thick or thin threads of molten glass trailed on the surface to produce simple coil accents, zigzag patterns, undulating "whisker" trails or complex sculptural effects.

Similarly, blobs of molten glass (usually dark blue) could be fused onto the vessel surface either in simple chains or in complex geometric arrangements. Decorative glass attachments of contrasting colors could be fused to the warm glass vessel also. These could be molded elements such as rosettes, lion-heads, theater masks, and the like (Pl. 16); or they could be free-blown attachments. Applied elements were often set at the base of the vessel's handle. Sometimes they were used all over the vessel's surface, however.

Once cooled, glass vessels could be decorated with cutting techniques performed with emery-fed wheels of different sizes. Essentially, these techniques exploited the structural similarities of annealed glass to compactly grained stone. Undoubtedly, there was a good deal of overlap between artisans who specialized in gem-carving and those who cut and engraved glass. This is no where more evident than in glass cameo work. Blanks for glass cameo vessels were made by casing dark (usually blue) glass with opaque white glass.

上一页 [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] 下一页

|